Secrets Behind 9,000-Year-Old Skeletons In Turkey Revealed

New discoveries have been made about the method that residents of the earliest city in the world in Çatalhöyük, Turkey, performed burial rites on the deceased. The discoveries were conducted by an international team with the participation of the University of Bern.

Famous for being world’s earliest metropolis, the Neolithic community expands to an area of 13 ha, decorated with densely aggregated mudbrick structures. The houses here provide archaeological proof of ritual practices, such as intramural burials with some skeletons having evidence of colorants and wall paintings.

Records have indicated the connection between the use of colorants and symbolic practices, among many past and present human societies. The use of pigments in architectural and burial situations grew particularly frequent in the Near East from the 2nd half of the 9th and the 8th millennium BC.

The latest research was conducted by an international team with Bern participation. Marco Millela, senior author of the study from the Department of Physical Anthropology, Institute of Forensic Medicine, University of Bern, said, “These results reveal exciting insights about the association between the use of colorants, funerary rituals and living spaces in this fascinating society.”

Daily activities at the Department of Physical Anthropology involve identifying the age and gender, examining violent injuries or particular treatment of the corpses, and resolving skeletal puzzles. Red ochre was most commonly used at the site, appearing on men, women and children, while cinnabar and blue/green were used for males and females, respectively.

Surprisingly, the quantity of graves in one structure seems to match with the quantity of subsequent layers of architectural paintings, indicating a contextual relationship between burial deposition and application of colorants in domestic space. Milella believes that this means when the people buried the deceased, they also painted on the building walls.

Moreover, at Çatalhöyük, some individuals “stayed” in the community: their skeletal elements were retrieved and circulated for some time, before they were buried again. This second burial of skeletal elements was also accompanied by wall paintings.

According to Marco Milella, “the criteria guiding the selection of these individuals escape our understanding for now, which makes these findings even more interesting.

Our study shows that this selection was not related to age or sex”. What is clear, however, is that visual expression, ritual performance and symbolic associations were elements of shared long-term socio-cultural practices in this Neolithic society.

Source: University of Bern

Source: University of Bern

Skeleton of a male individual aged between 35 and 50 years old with cinnabar painting on the cranium.

The deceased’s skeletons were partly painted, dug up numerous times and reburied. The discovery grants deeper comprehension into how members of an intriguing society buried their dead 9 millennia ago in Çatalhöyük, central Anatolia, Turkey, one of the most significant archaeological locations in the Near East.Famous for being world’s earliest metropolis, the Neolithic community expands to an area of 13 ha, decorated with densely aggregated mudbrick structures. The houses here provide archaeological proof of ritual practices, such as intramural burials with some skeletons having evidence of colorants and wall paintings.

Records have indicated the connection between the use of colorants and symbolic practices, among many past and present human societies. The use of pigments in architectural and burial situations grew particularly frequent in the Near East from the 2nd half of the 9th and the 8th millennium BC.

Source: University of Bern

Source: University of Bern

Detail of the cinnabar stripe on the cranium of the male individual.

A huge body of evidence of complicated and enigmatic symbolic practices has been returned thanks to Near Eastern archaeological locations from the Neolithic Period. The evidence includes secondary burial treatments, retrieval and circulation of skeletal parts including skulls and the employing of pigments in both architectural spaces and funerary situations.The latest research was conducted by an international team with Bern participation. Marco Millela, senior author of the study from the Department of Physical Anthropology, Institute of Forensic Medicine, University of Bern, said, “These results reveal exciting insights about the association between the use of colorants, funerary rituals and living spaces in this fascinating society.”

A time travel into a world of colors, houses, and dead

Marco Milella was part of the anthropological team who excavated and studied the human remains from Çatalhöyük. His work involves trying to make ancient and modern skeletons “speak”.Daily activities at the Department of Physical Anthropology involve identifying the age and gender, examining violent injuries or particular treatment of the corpses, and resolving skeletal puzzles. Red ochre was most commonly used at the site, appearing on men, women and children, while cinnabar and blue/green were used for males and females, respectively.

Source: University of Bern

Source: University of Bern

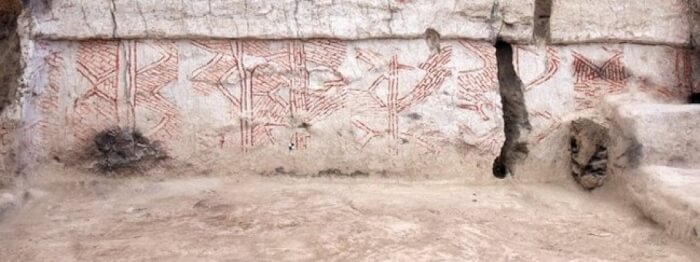

Geometric wall painting in the building.

Intriguingly, the number of burials in a building appears associated with the number of subsequent layers of architectural paintings.Surprisingly, the quantity of graves in one structure seems to match with the quantity of subsequent layers of architectural paintings, indicating a contextual relationship between burial deposition and application of colorants in domestic space. Milella believes that this means when the people buried the deceased, they also painted on the building walls.

Moreover, at Çatalhöyük, some individuals “stayed” in the community: their skeletal elements were retrieved and circulated for some time, before they were buried again. This second burial of skeletal elements was also accompanied by wall paintings.

Neolithic mysteries

Only a selection of individuals was buried with colorants, and only a part of the individuals remained in the community with their circulating bones.According to Marco Milella, “the criteria guiding the selection of these individuals escape our understanding for now, which makes these findings even more interesting.

Our study shows that this selection was not related to age or sex”. What is clear, however, is that visual expression, ritual performance and symbolic associations were elements of shared long-term socio-cultural practices in this Neolithic society.

Share this article

Advertisement