9 Recent Mysterious Archaeological Findings That Baffle Scientists (Part I)

1. Regal perfume of Queen Cleopatra

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Source: Wikimedia Commons

According to Ancient Egypt Online, the first time the word "Kyphi" (meaning temple’s religious incense) appeared in the pyramids was in between the 5th and 6th dynasties of the Old Kingdom of Egypt (from 2686 – 2181 BC). While these inscriptions does not provide any recipe for creating Kyphi, or list out any specific ingredients, they make it clear that Kyphi was one of the luxuries that pharaohs used on their journey toward Kingdom Come.

Source: Pinterest

Source: Pinterest

According to the Mysterious Universe website, the document records: “After the assassination of Julius Caesar, Cleopatra left Rome to become the queen of Egypt. There she greeted Mark Antony, a Roman politician, on a ship with perfumed sails. Cleopatra’s arrival was announced by clouds of perfume before her barge came into view.” Therefore, Cleopatra's signature perfume is always a mystery sought to be discovered by later generations.

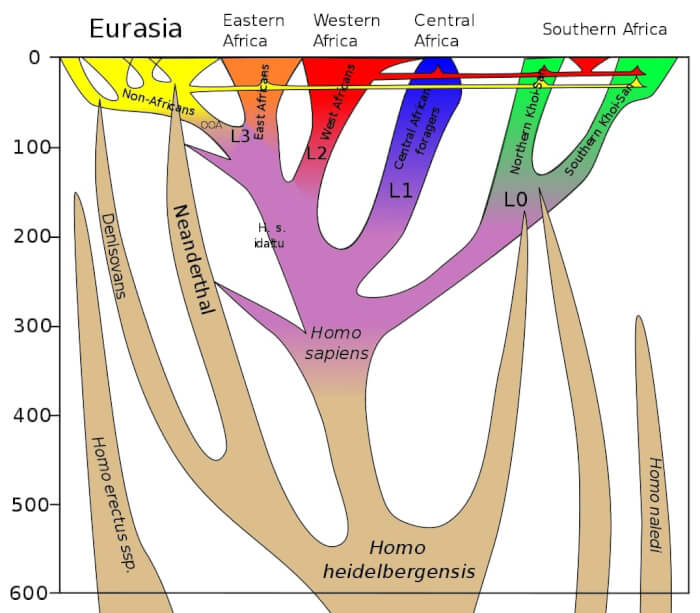

2. Ancient hominid interbreeding

Source: Pinterest

Source: Pinterest

In 2017, Rogers led a study which found that two lineages of ancient humans, Neanderthals and Denisovans, separated much earlier than previously thought and proposed a bottleneck population size. It caused some controversy—anthropologists Mafessoni and Prüfer argued that their method for analyzing the DNA produced different results. Rogers agreed, but realized that neither method explained the genetic data very well.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The new study has solved that puzzle and in doing so, it has documented the earliest known interbreeding event between ancient human populations—a group known as the “super-archaics” in Eurasia interbred with a Neanderthal-Denisovan ancestor about 700,000 years ago. The event was between two populations that were more distantly related than any other recorded. The authors also proposed a revised timeline for human migration out of Africa and into Eurasia. The method for analyzing ancient DNA provides a new way to look farther back into the human lineage than ever before.

“We’ve never known about this episode of interbreeding and we’ve never been able to estimate the size of the super-archaic population,” said Rogers, lead author of the study. “We’re just shedding light on an interval on human evolutionary history that was previously completely dark.”

3. Long-lost chapel discovered in Auckland

Source: Durham Archaelogy

Source: Durham Archaelogy

The chapel was demolished in the 1650s, after the Civil War, and, although its remains were known to exist at Auckland Castle, the exact location remained a mystery until it was revealed by research carried out by The Auckland Project and Durham University.

Source: Andy Gammon Art & Design

Source: Andy Gammon Art & Design

Several beautiful artefacts were discovered that reflect the high-status ecclesiastical occupation of the site, including two book clasps, an enamelled mount possibly depicting St Cuthbert, and what is believed to be a part from stained-glass working equipment, made from extremely rare baleen (whalebone). A few examples of imports from continental Europe were also found, including the enamel band of a liturgical vessel from Limoges, and a wine glass with shell decoration of Iberian design.

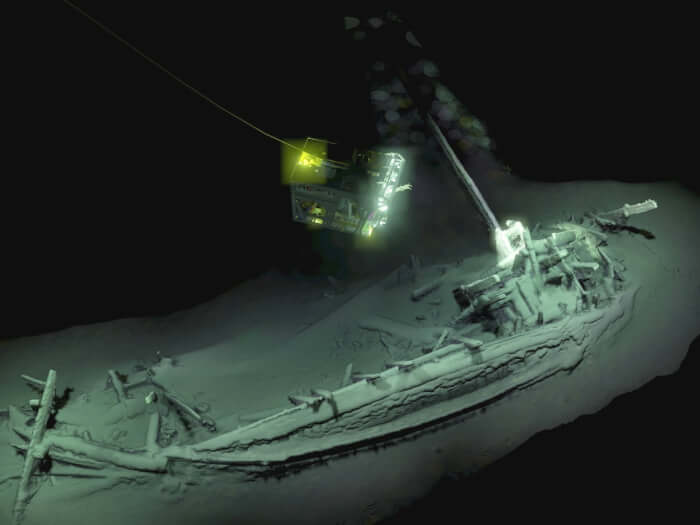

4. World’s oldest intact shipwreck

Source: YouTube

Source: YouTube

The 23-metre (75ft) vessel, thought to be ancient Greek, was discovered with its mast, rudders and rowing benches all present and correct just over a mile below the surface. A lack of oxygen at that depth preserved it, the researchers said.

Source: Pinterest

Source: Pinterest

The ship is believed to have been a trading vessel of a type that researchers say has only previously been seen “on the side of ancient Greek pottery such as the ‘Siren Vase’ in the British Museum”.

Share this article

Advertisement