78,000-Year-Old Child Burial Revealed Africa’s Oldest Known Human Grave

Around 78 millennia ago, a child roughly 36 months old from an East African community was buried into a shallow pit, having its small body curled by caretakers, and possibly the head rested on a pillow before being committed to the earth.

Recently, a new research related to the dig of the child’s burial uncover the earliest proof of modern humans in Africa entombing the deceased. Paul Pettitt, an Old Stone Age archaeologist from Durham University said, “It's beautifully excavated… and there can be no dissension that it's a burial.”

The archaeologist whose research has focused on prehistoric burial rituals, yet not involved in the work added, “It shows that the tradition of burying some of the dead … probably arose from a common custom amidst Homo sapiens in Africa."

Furthermore, scientists were able to discover graves of modern humans and Neanderthals approximately 120,000 years old in Eurasia. However, those graves consisted of peoples hardly contributing to humans living in the present-day.

Scientist discovered the new burial in 2013 beneath the rocky overhand of a cave known as Panga ya Saidi along the coastline of southeastern Kenya, when a strange pit-shaped undulation of sediment was spotted within the walls of one of the trenches built by archaeologists and local workers.

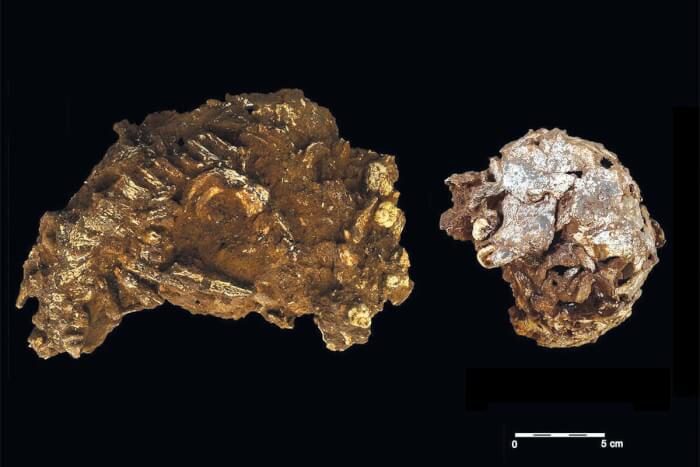

Upon the examination, a small bone fell out and promptly turned to dust. Knowing that they had discovered extraordinarily exquisite remains, archaeologists spent the next 4 years painstakingly excavating and arranging the fragile bones in plaster. Later, analysis of two teeth at the National Museums of Kenya revealed the body as a human child.

The way the child passed away could not be figured out, but the posture indicated that it was exquisitely curled into a fetal position before being placed into a shallow pit, all done by caretakers, according to Michael Petraglia, archaeologist from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

The remains might have been tightly wrapped in a shroud-like material, indicated by its torqued shoulder. Additionally, the skull was probably propped up on some types of pillow that gradually decayed, suggested by how it twisted and bent within the burial.

Petraglia claims that it’s feasible to believe that human mortuary practice possibly originated from Africa before becoming global traditions as the continent residents start to travel around the world. The theory is backed up with complicated symbolic behaviors, consisting of jewelry use and ochre pigment decoration believed to emerge from Africa 125,000 to 100,000 years ago.

He thinks that it’s still ambiguous whether Neanderthals started to bury their deceased on their own or these customs originated from the common ancestor of them and humans. Furthermore, Petraglia indicates that half of such prehistoric graves include children.

Julien Riel-Salvatore, an anthropologist at the University of Montreal, agrees that the level of care that went into Mtoto's burial suggests a child's death was especially poignant. "The idea that people would go out of their way to preserve the child's body, which would slow its decay and protect it from scavengers, reflects the fact that people cared deeply about their children," he says.

More burials from the region and time period will need to be discovered before researchers can start to puzzle out the significance that burial held to these ancient humans, says Louise Humphrey, an anthropologist at the National History Museum in London. Still, she says, the tenderness of the burial in Panga ya Saidi reveals "an expression of personal loss"—a sorrow that transcends time.

Recently, a new research related to the dig of the child’s burial uncover the earliest proof of modern humans in Africa entombing the deceased. Paul Pettitt, an Old Stone Age archaeologist from Durham University said, “It's beautifully excavated… and there can be no dissension that it's a burial.”

The archaeologist whose research has focused on prehistoric burial rituals, yet not involved in the work added, “It shows that the tradition of burying some of the dead … probably arose from a common custom amidst Homo sapiens in Africa."

Source: Fernando Fueyo

Source: Fernando Fueyo

Furthermore, scientists were able to discover graves of modern humans and Neanderthals approximately 120,000 years old in Eurasia. However, those graves consisted of peoples hardly contributing to humans living in the present-day.

Scientist discovered the new burial in 2013 beneath the rocky overhand of a cave known as Panga ya Saidi along the coastline of southeastern Kenya, when a strange pit-shaped undulation of sediment was spotted within the walls of one of the trenches built by archaeologists and local workers.

Upon the examination, a small bone fell out and promptly turned to dust. Knowing that they had discovered extraordinarily exquisite remains, archaeologists spent the next 4 years painstakingly excavating and arranging the fragile bones in plaster. Later, analysis of two teeth at the National Museums of Kenya revealed the body as a human child.

Source: Nature

Source: Nature

The way the child passed away could not be figured out, but the posture indicated that it was exquisitely curled into a fetal position before being placed into a shallow pit, all done by caretakers, according to Michael Petraglia, archaeologist from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

The remains might have been tightly wrapped in a shroud-like material, indicated by its torqued shoulder. Additionally, the skull was probably propped up on some types of pillow that gradually decayed, suggested by how it twisted and bent within the burial.

Source: Mohammad Javad Shoaee

Source: Mohammad Javad Shoaee

Petraglia claims that it’s feasible to believe that human mortuary practice possibly originated from Africa before becoming global traditions as the continent residents start to travel around the world. The theory is backed up with complicated symbolic behaviors, consisting of jewelry use and ochre pigment decoration believed to emerge from Africa 125,000 to 100,000 years ago.

He thinks that it’s still ambiguous whether Neanderthals started to bury their deceased on their own or these customs originated from the common ancestor of them and humans. Furthermore, Petraglia indicates that half of such prehistoric graves include children.

Source: Nature

Source: Nature

Julien Riel-Salvatore, an anthropologist at the University of Montreal, agrees that the level of care that went into Mtoto's burial suggests a child's death was especially poignant. "The idea that people would go out of their way to preserve the child's body, which would slow its decay and protect it from scavengers, reflects the fact that people cared deeply about their children," he says.

More burials from the region and time period will need to be discovered before researchers can start to puzzle out the significance that burial held to these ancient humans, says Louise Humphrey, an anthropologist at the National History Museum in London. Still, she says, the tenderness of the burial in Panga ya Saidi reveals "an expression of personal loss"—a sorrow that transcends time.

Share this article

Advertisement